Volume 17

Support the families of Marlene Valdez Pace, Meshay Melendez and Layla Stewart; Resham interviews Funeral Director and Death Doula, Lily Sage Weinrieb; Men in Black line dance

ACTION ITEMS

Marlene Valdez Pace, mother of three, died on March 23 surrounded by family. Her niece writes on her gofundme: “My aunt Marlene Valdez Pace, age 42, had a severe, unexpected stroke earlier this week while putting up cattle fence with her two sons. The boys heroically picked her up, loaded her into the truck and drove her to a waiting ambulance (even though none of them have a driver’s license)…Unfortunately, Marlene’s medical insurance had lapsed last year; and the life support costs as well as other medical bills and end of life costs are quite costly. Marlene had a lot on her mind this past year. One year ago, both of Marlene's parents, Lena and Marvin Valdez, also unexpectedly passed away, within one day of each other.” She remembers Marlene as “a brilliant, kind, beautiful, hardworking person who will be greatly missed by anyone who ever had the honor of gracing her presence whether it be cooking tamales with her, herding cattle, dancing under the stars, or having a deep conversation that would leave you laughing, crying, and a better person.”

Please join us in supporting Marelene’s family’s financial stability as they grieve.

SUPPORT THE FAMILY OF MARLENE VALDEZ PACE HERE

Meshay Melendez and her 7 year old daughter, Layla Stewart, were murdered by Meshay’s abusive ex-boyfriend. The two were missing for ten days before their bodies were found on March 22. Her ex had a history of violence and had previously broken a restraining order in an attempt to shoot Meshay. He was released on bail two days before she and Layla went missing. Meshay’s mother released a statement saying: “My babies were failed by the system.”

Meshay is remembered as as a loving mother. She and Layla were both “full of life.” Please join us in ensuring that their grieving loved ones are able to lay them to rest with the care they deserve. All funds raised will go towards funeral costs and legal fees as they seek justice for Meshay and Layla.

SUPPORT MESHAY AND LAYLA’S FAMILY HERE.

FUNDS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT FROM PREVIOUS VOLUMES:

KWELI AMARU SHAKUR’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

FRANK “PANCHO” AND CISCO’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

FELICITY SWAFFORD’S DAUGHTER IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

DAYANA BUSTILLOS HERRERA’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

ANDREW STANDIFIRD’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

TYRE NICHOL’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

TIABI RAUF’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

BRANDON’S MOTHER IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

LINDY CHRISTOPHER’S FAMILY IS STILL SEEKING SUPPORT

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Interview with Funeral Director and Death Doula, Lily Sage Weinrieb

by Resham Mantri

I met Lily in October of 2021 at the home of Amy Cunningham, my own father’s funeral director, and a deeply supportive and connective person in the world of funeral directors and death doulas in New York City, especially women. I was particularly impressed with the young funeral director women who had just been through a year and a half of mass dying in NYC of 2020. They had the air of having been through a war, and knew they survived it. They were intimidating, part of a club we could never know, smoking cigarettes, laughed and spoke very loud. In short they did not give a shit. I liked them. Lily was one of these people and we immediately hit it off. Since then we have worked together on funerals, created in-person death cafes and they have been a valuable resource to me, opening up the world of funeral homes and dying in NYC so I can be a better advocate for my death clients. I was so glad to get this opportunity to sit in Lily’s Greenpoint home, among all her own art and art which they have acquired from the dead. The interview is so necessary (for New Yorkers, for people interested in death work, and for anyone interested in what happens when we die) that I could not get the piece any shorter than 9 pages. The interview in its entirety is linked here, and below are shorter pieces of the interview I loved. We are so excited to share this conversation with you and also herald an exciting new shift in this Digest. (More to come!)

Andrew Kelly did a series titled the “Female Undertakers of Harlem” which documents Lily and her then coworkers in a particular moment in time. These people worked during the most intense period of recent Covid death in NYC of 2020. These photos are from that series.

Segments of our Conversation:

LSW: I'm Lily Sage Weinrieb.

I'm a licensed funeral director in the state of New York, so that means I am a mortician and embalmer, these are all things that you have to do to be licensed. As a funeral director in New York, I can sit with families to make funeral arrangements. I can pick up the person who's died from wherever they've died. I can embalm their body or preserve them using other means. I can go to cemeteries and crematories and make sure that they are buried or cremated properly.

I'm also a death doula, so I work with families. When I say family, I mean that with both a capital and a lower case f. People ask me to define family.

LSW: I say anybody who could go into your refrigerator without having to ask. To me that's most people I've met on the street.

LSW: I decided that I wanted to intervene actually. I started to view end of life care, like death care as radical, and I view it as activism, because you can change the trajectory of generational trauma by intervening and creating space for ritual grief.

To be a licensed funeral director, which gives you the privilege of working with grieving families, immediately following a death, the trajectory looks different depending on what state you live in but ultimately there's a national board that accredits college programs. They are almost exclusively at community colleges. There are some states that offer four year degrees. If you are in a state like Michigan that offers a four year degree in mortuary science, do it, because it is so worth it to spend the time studying this and thinking about it and being in community with thinkers. Don't rush to get into the rest of your life.

RM: How did you come to death doula work?

LSW: My grandmother's adoptive brother's daughter, I call her my Aunt Jessica. She’s always been the cool aunt. She's incredible. She had ovarian cancer. She had been living with ovarian cancer for six or seven years. Yeah. And when I was a senior in college, Jess called me and she's like, I'm dying. I want to spend time with you before I die. I said, well, I want to spend time with you and I don't want you to die. And she said, I actually don't want to talk about not dying. I want to talk about having a good death. I said, what's a good death? And she said, well, just come to New York and talk about it.

I was 22, her daughter Emma was 12 and Jessica's ovarian cancer had metastasized and spread and it was no longer treatable. And so she was dying and she wanted what she called a good death. She's always been a really impressive patient advocate. And I stood by her side and was like, I want to take up arms with you and fight this fight for you to have a good death.

What that meant to her was dying at home, dying consciously, getting a chance to say goodbye to all of her friends and have a party before she died, so that she didn't have to have a funeral after she died. That was one of the first funerals I organized, not an after-death funeral, but a life party.

RM: I know you worked as a funeral director, mortician, death doula, death worker during the pandemic, specifically right at the start of it in 2020 in New York City. What, if anything, has working with the dying during a global pandemic taught you? Are there any lessons as a collective we should be taking from this moment?

LSW: But I learned as a collective, we need to advocate for our rights. As a workforce, as people who exist. We may not be seen, but we are important. The fact that I was having to basically barter masks from hospital staff because our masks and glove supply was bought out by them was really upsetting.

LSW: And I also had a rule where I wouldn't send these [photos] without being on the phone with the family. Right. So I think the way that we can do this work is different. The way that I take care of people is trauma informed. I am actively training other funeral directors in how to do this, but it's not an easy thing to do and you can't step on people's toes. And so the way I do it is just by example. By refusing to send a photo that I don't believe is appropriate or by refusing to send a photo without being physically on the phone with somebody.

RM: I I hear you saying just that there's moments even within a mass death and global pandemic to create softness or care.

LSW: Yes.

LSW: But you cannot do it without accompanying them. This is critical. Most of the time as funeral directors, we are sort of taught to walk the family into the chapel where their loved one is all the way down at the end and sort of leave them there, which to me is like wild. Most folks have not had an experience with death. And even if they have, you know what, every death is different.

LSW: Sometimes it's enough to just be in the presence of that person's body and there will be nothing else. And that is beautiful. Sometimes people want to interact with them. So the first thing I do is I go up, I start sort of by the foot side of the person and I gently rest my hands on their hands on the hands of the deceased or the chest of the deceased and again mirroring, allowing people to see that it is safe. That it is okay.

RM: Why do you think it’s important to give people something to do?

LSW: Because that's doing the work of grief work. If you are participating, if you are actively taking care of that person, then you know what you did when they died. Their death didn't just happen to you. Their death happened and you did what? That is a very different narrative. That’s when that combats trauma.

RM: I love that.

LSW: The sheer question from a professional, somebody in my position, which wields a lot of power, saying “Will you help me with that?” It gives so much and it is not mine to take in the first place. Who the heck am I taking it? So a lot of what I do is just give back. Not every family wants it. That’s fine. But you gotta offer.

RM: I'm thinking about this moment where a lot of death doulas are talking about reclaiming ritual around death from our own ancestries. Under capitalism and white supremacy so much has been taken from us. You are in a unique position to create moments of ritual and offer them to families.

LSW: That is my ultimate goal. To create ritual. I don't care what it is, and people do not always know what their rituals are. So I will make space for them. I keep like a little thing of essential oils. Candles are a good one. We can carry them with flowers. Oftentimes I'll say is there anybody here that is not here with their body, but we would like to make sure we honor them and we'll place a flower with them for that person. I love that humans can do that. We have language.

RM: You're in a unique position within New York City to see how people actually die. What do you think would benefit New Yorkers to know about how people die here?

LSW: People should know that any funeral home you ask won't charge you to spend 20-30 minutes with the person who's died. They're not gonna be embalmed to make that happen. If you want to dress that person, you may do so. You are entitled to that. Now the funeral home will say, well, do you want us to dress them? And you can say no. The funeral home may say, well we don't allow families to do that. You can ask Why?

I think dying in New York is special because you join a lot of people who do it every day, just like everything else in New York. Yesterday was a really busy day in New York for death, we took on nine new calls. That is crazy town. And this happens in death. I don't know why. It happens with births too. From what I understand is like, there will be like lulls and slow periods and then all of a sudden boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. Everybody's like, I don't know what happened today, but everybody decided to die.

There is an element of decision in there because I do believe that dying people have an element of choice. The number one thing dying people need is not water or morphine or comforting touch. It's actually permission. I say that to families all the time.

LSW: Also in New York, it is important to know there are options for non-binary and gender nonconforming individuals on the death certificate. Even if you do not have your name legally changed, the medical examiner's office will honor your name. You do not have to be dead-named in death.

LSW: People buried on Hart island are buried in large plot graves, low-key they're mass graves, absolutely. It is also important to note they are buried by inmates on Rikers Island. The people doing this work are people who are incarcerated.

RM: I know that you have so many passions, interests in addition to your death work that you also bring into your death practice! Can you talk about other work that you're doing? Things that bring you joy?

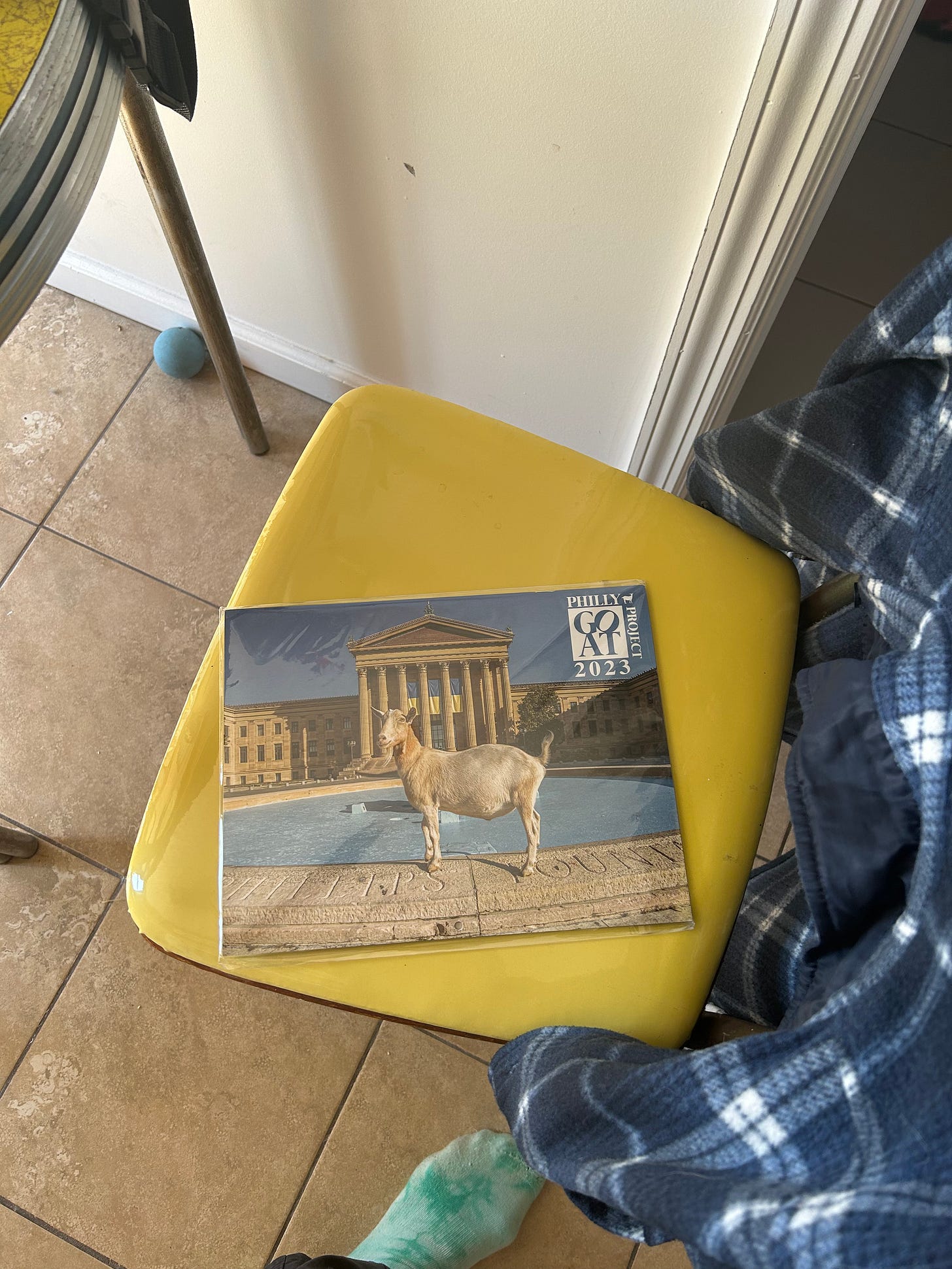

LSW: So I, I helped start and run an urban agricultural program in Philly called the Philly Goat Project with my mom. So we've got 13 goats in the city of Philadelphia, and they're trained as therapy animals, and they're wonderful. And it's a intergenerational community based program.

I’m also an artist, fourth generation on my mom's side. I've been working a lot in plaster lately. I don't know why, but I'm kind of obsessed with like lighting and the way that like the gauze plaster can be illuminated and look so warm even though it's cool to the touch.

Images from Lily’s home:

OFFERINGS WE LOVE

Floripondio is a new intentional deathcare offering in the Bay Area. Batul True Heart and Melissa Reyes “are traditional healers, community herbalists, and death companions. We are Indigenous and Queer. We each bring over 20 years experience working with various healing modalities, training with elders and mentors, exploring our own experiences of ancestral loss and reconnection, teaching, and holding ceremonial space for our community.

We are committed to advocacy and supporting our people to understand their options and feel a sense of respect, honor, and dignity as they navigate this journey. Although we know death cannot be cured, we believe that when given the proper conditions, the end of life can be a healing experience for everyone involved.” (from the Floripondio website)

They are offering a Death Cafe for QTBIPOC on Tuesday, April 18th.

Find out more and register here!